Also, I have no idea why the font is being so screwy.

*****************************************************************************

There are three concepts that, when one looks closely enough, can be seen as a single indivisible triad: narratives, context and memory. They all fundamentally deal with an associative way of thinking and they are noticeably robust: one doesn’t easily forget things (my cousin and I still occasionally debate who was at fault in a scuffle we had when I was seven) and we seem to understand things best when they’re told as a story. They also have another trait in common: they are often lacking if not non-existent when I try to find information from the internet.

Take Wikipedia as an example. It certainly has a wealth of raw information; just about anything one can think of seems to have an article, whether your interest is in hermetian matrices, hardcore bands, Lacanian psychoanalysis or Pokemon trading cards. Even so, I never feel the same sense of fulfillment reading material on Wikipedia that I get from reading a book; I often find myself struggling to walk away with something to hold on to after browsing through this seemingly infinite pool of collective knowledge.

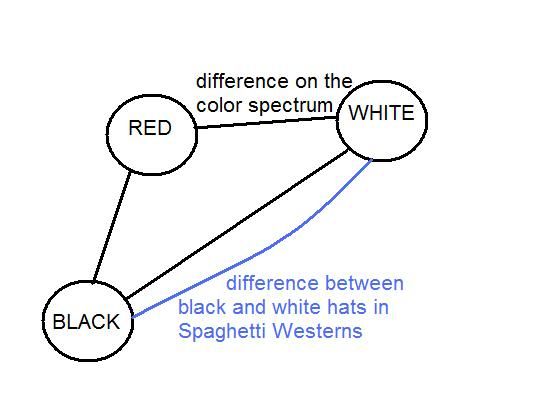

Maybe I’m just of a dying breed of people who hold on to physical books, but more universal reasons seem to be at play. Our brains work in an associative manner; rather than record our memories in a serialized manner like a video camera or a computer’s hard drive, we create memories by connecting various objects, sensations, thoughts, images, sounds and other past experiences. Conversely, we recall memories from the past by seeing, hearing, feeling or thinking something that we’ve associated with it; anyone remember the scene that everybody talks about from Swann’s Way where the narrator takes a bite of a Madeline cookie and his entire past rushes back at him?

A single sensation or reference brings back a rapid cascade of memories and this same phenomenon underlies what might be our memory’s inherent preference for books: we associate its content with the distinct look and feel of the book’s cover, pages, printing, wear and tear. Simply put, you can remember something much better when you attach it to a physical object of some kind.[1] But just as the physical context of knowledge may matter more than we think, so too might the relevance of that knowledge to some larger narrative. The journalist Malcolm Gladwell might oftentimes be criticized for the lack of empirical rigor behind his theses, but I prefer any one of his books to a series of entries on Wikipedia because I believe him to be a masterful storyteller able to weave a larger number of data, anecdotes and ideas into a single story that makes sense of them. Knowledge is much more easily remembered when there is a narrative that brings it all together.

One way of thinking about this is that a narrative introduces redundancy to knowledge. It’s much easier to remember an idea when it’s linked to a number of other ideas as part of a larger theory. If you learn something in a vacuum, there will be nothing to give you any clues to it should you forget it; but by relating it to something else, we have something to remind us of the original idea.

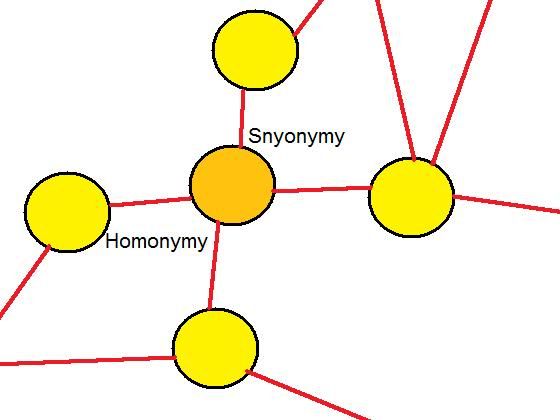

But is it really the case that there are no narratives on Wikipedia? If I look up David Bowie, I’ll find a summary of his life and career and with it there will be hyperlinks to more detailed summaries of particular works or to biographies of his contemporaries; there’s definitely a narrative. Even so, there’s something about Wikipedia that is too summarized and distilled to be the kind of story that sticks well after I’ve finished reading an article. It offers not so much a story as a summary in which details are relegated to the various articles that it links to.

But these links on Wikipedia are inadequate to finish telling the story. They are details that are told in a complete vacuum, unaware of the fact that I came from a page talking about one thing and not another. In Malcolm Gladwell’s Blink, the defeat of the United States Navy 7th Fleet at the hands of Paul Van Riper’s meager force in the 2002 Millennium Challenge War Games is talked about in the context of how human intuition can be more powerful than the world’s greatest computers, but a Wikipedia article summarizing the thesis of Blink could only tell it in sufficient detail by providing a link to an unrelated page summarizing the incident; one that would fail to have the interpretive richness of Malcolm Gladwell’s own retelling.

A story, as opposed to a simple summary or functional narrative, speaks to us about what is not obvious. Whereas summaries compress, stories interpret by bringing together a wealth of information and constructing a unique idea. Furthermore, through this same process of bricolage, a story is filled with a rich variety of prose and impedimenta that allow us to create a rich network of associations and have an experience that is eminently memorable. A summary, as a simple compression of one or more stories, simply doesn’t have the same informational richness as those stories and as such cannot create the strong mnemonic associations that stories do.

At the end of the day, storytelling is something that is hardwired into us. We comprehend and remember things as stories, not data, and the tradition of storytelling has been a universal ritual as far back as recorded history takes us. This natural affinity of ours towards telling stories can teach us a lot about how we learn and should be taken into consideration as we expand our educational tools into the domains of the internet and cloud computing. The ability to express ideas as dynamic and interactive programs as opposed to static texts and the interconnection of vast amounts of user-created data will doubtless allow us to inform and educate in novel ways; but these innovations must cultivate the human faculty for storytelling if they are to be truly effective as pedagogical tools. As our world becomes increasingly interconnected and hyper-abundant in information, context has become the essence of knowledge; and one cannot understand context without understanding stories.

[1] For further reading on this idea, see Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s notebook, Opacity (http://www.fooledbyrandomness.com/notebook.html)